|

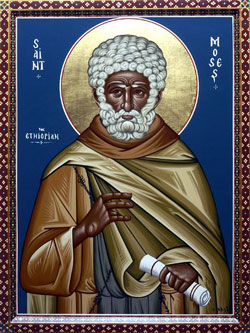

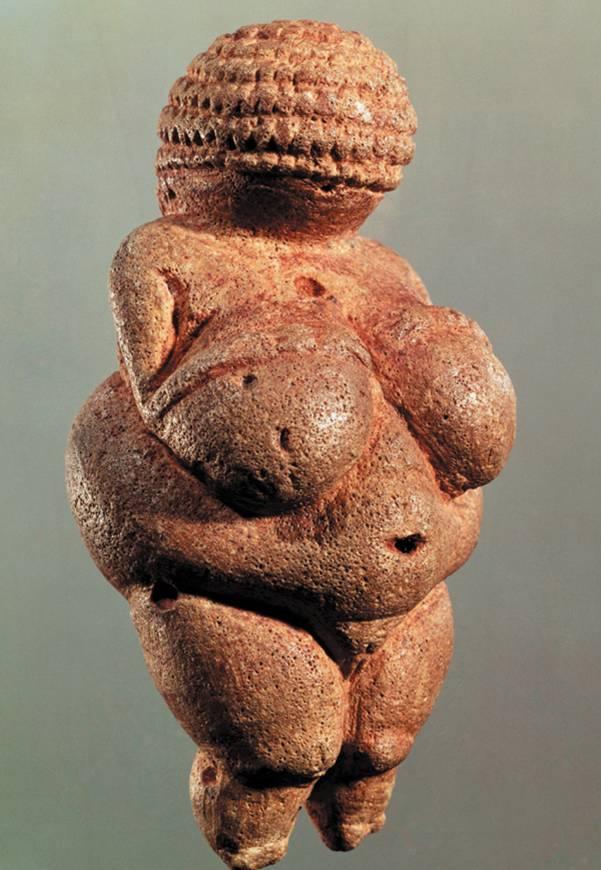

THE IMAGE CONSTRUCTION OF G-D AND THE DECONSTRUCTION OF THE WHITE NORMATIVE THEOLOGICAL GAZE: AN ART HISTORICAL SURVEY “The beautiful, almost without any effort of our own, acquaints us with the mental event of conviction, and so pleasurable a mental state is this that ever afterwards one is willing to labor, struggle, wrestle with the world to locate enduring sources of conviction — to locate what is true.” -Elaine Scarry When G-D is always depicted as a white man, it becomes difficult to imagine G-D as being anything else. For too long the church has allowed culturally normalized and limited depictions of our creator to dominate the landscape. This restricted view of G-D not only promotes incorrect racist theology, but limits our understanding of the Divine Mystery. Historically Christian art has propagated a very specific one-sided view of G-D and this has concrete ramifications of exclusion and limitation; I propose that contemporary art is specifically challenging this by presenting G-D as black and a woman. This paper will first examine the historical depictions of G-D, while discussing how images of G-D construct our understanding of self in relation to G-D, and reflect on the hope presented by the contemporary work being produced. When taking a historical survey of art we encounter a plethora of deistic representations. Most cultures and religions seek to represent their god with imagery. The notable exception to this being the Muslim prohibition of anything that might be construed as god: nothing with heartbeats, which accounts for the floral motifs common in the predominately Muslim Middle Eastern nations. This exception aside, consider the Venus of Willendorf, commonly acknowledged as one of the first pieces, if not the first piece, of art on record. She is a fertility goddess with exaggerated bulbous breasts and buttocks. With her, some of the first known art depicts humans seeking to communicate with G-D, looking for reproductive favor. This shows how humans place such a premium on communication with G-D and will do it through all available means. Not just with spoken or written word, or physical action, but also sculptural depiction. This seeking of relationship and connection with the divine Creator is innate and present from our earliest records. Regarding the discussion of pictorial depiction and race it is crucial to understand Moses of Ethiopia’s importance and how limited acknowledgment by the academy is indicative of a much larger problem. Moses of Ethiopia, also known as Moses the Black, was a Desert Father of Scetis, who was later martyred. With his depiction there is the rare occurance of a Black religious figure in the canon of art. In Moses of Ethiopia we have a correct alignment of illustration and historicity. Given the richness of the Desert Father tradition it is disappointing that so minimal attention is paid to Moses of Ethiopia, with relatively little scholarly research on him. This shows just how far into the liminal periphery black depictions of religious figures are relegated. When not acknowledged by the academic establishment, let alone the ecclesiastical one how do these stories become acknowledged and known? By pushing the liminal into the central. Saint Moses ordination to the diaconate provides a fascinating point of discussion on the concept of the colors, white and black, as relating to morality. “After many years of monastic exploits, Saint Moses was ordained deacon. The bishop clothed him in white vestments and said, ‘Now Abba Moses is entirely white!’ The saint replied, ‘Only outwardly, for God knows that I am still dark within.’” This emphasis on the color of Moses during his ordination is typical of the dominate “white is right” rhetoric prevalent in the discussion of sin; blackness being associated with sin. Worth noting in this quote is that the Bishop is constrained to a black/white rhetoric while Saint Moses refers to the darkness, the absence of light, the separateness from G-D. This references the concept proposed by John the Evangelist in his first epistle, “This is the message we have heard from him and proclaim to you, that God is light and in him there is no darkness at all.” This movement away from a black/white binary places the discussion of morality centrally, as opposed to the emphasis on color of vestment or skin. Moving forward into the Middle Ages and to consideration of iconographic representations, it is important to remember that this culture was mostly illiterate and that imagery was the dominate, if exclusive “reading” material for most individuals. Roland Recht explains it most succinctly when he states, “Developments in medieval science and natural philosophy elevated sight about the other senses, deeming it the basis of empirical truth.” When the people encountered a depiction of G-D, or the saints, the image was authoritative. Imagining G-D as something other than the depiction would be heretical, as the priests interpretive espousal and the image had no personal information or learning to contradict this specific interpretation. This lack of literacy allows for an almost totalitarian control on which aspects of theology are discussed, let alone promoted. This rigid control allows for the propagation of a normative white depiction of G-D. The educated people of the Middle Ages are complicit in false interpretation and propagation. While there are myriad reasons for this, chief among them are the feudal based income and protection systems; livelihood being tied into the prevalent rhetoric, as the feudal system promoted systematic adherence to those in a higher economic class with their concurrent position of authority. It is worth noting that the priests exerted a lot of control regarding the course of conversation. Priests were educated and had the ear of the patrons. Inherent in this relationship, though, is a power dynamic. The patron provides wealth and resources, the priest provides salvation via indulgences and the promise of shorter time in purgatory for a monetary price. Precarious is the balance, however, because if the priest steps over the proverbial line, the coffers will close. This takes away any incentive for proclaimation against the dominate rhetoric. During the Middle Ages and continuing through the Renaissance, the wealthy commissioned artists to produce illustrative religious images. The patrons portraits are then placed on saints faces or among the devoted. This is clearly illustrated in The Ghent Altarpiece by Jan Van Eyck. The patrons, Joos Vijd and Elisabeth Borluuare (his wife), are included in full-bodied portrait form on the closed wings of the altarpiece. The Ghent Altarpiece is influential catechesistically because of the words included around G-D. “This is God, all powerful in his divine majesty; of all the best, by the gentleness of his goodness; the most liberal giver, because of his infinite generosity… On his left, security without fear.” To get to these benevolent words it is necessary to literally push the patrons out of the way to get to the gracious depiction of G-D on the inside. The patrons, depicted alongside the saints, are the guardians of the G-D imaged inside. It is imperative to remember that this is the construction of human mind and understanding. To see no one depicted in the church imagery, not in the deistic representations or even among the faithful, that is of a different skin tone and to have recognizable portraits of the oppressors portrayed is problematic theologically. Regarding the theological underpinnings, it is lovely to think of art and writing as being divinely inspired, but it is far too frequently the creation of the limited human understanding. This human constraint remains throughout history and continues to confine the scope of understanding. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance the artists payment was directly tied to the patrons pleasure and this ensures that the dogma of the ruling class remains prevalent in the depictions present in all of the public and private worship spaces. Since most of the Christian art being produced was coming from Europe, with its preponderance of white skin, the dominant motif was pale faces. With the creation of a workable printing press in the 1440’s there is a dispersal of written text and rise of personal books, but this is limited in its scope for some time, leaving images to continue the work of education with their constrained depictions of G-D and the faithful. The tide of iconoclasm coincides with the Age of Discovery and global expansion. With the concurrent rise of the slave trade and the integration of a more diverse global population, increasing concerns must be raised about this limited depiction of G-D. When presented with imagery that not only mirrors, but re-enforces the prevailing theology of oppressive whiteness there is an exclusionary measure at work that is not in line with Biblical truth. While it is possible to think that the iconoclastic movement is helpful, in that it aids the demolition of the normative white theological bias, this does not allow for the fact that the iconoclastic movement while strong, was not successful in the destruction of all religious imagery. The effect of the iconoclastic removal of images from churches is something from which the ecclesiastical body has yet to recover. The church used to be the leading patron of the arts and with this relinquishment the church has lost a key portion of influence. However, the iconoclastic movement and the loosening of the churches grip on culture is what allows for the creation of new imagery today. Moving into contemporary art there are glimpses of hope. Harmonia Rosales is reinterpreting Renaissance masterworks with Black heroines. By taking the Creation of Adam by Michelangelo and making the main characters Black and female, and calling it the Creation of God, the dialogue is allowed to expand. Rosales explicit title, Creation of God, firmly cements this piece within the racial construction of G-D dialogue, inspite of its almost heritical title. The Creation of Adam is famous not only because of its location on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, the center of Roman Catholic worship, but also because of the languid posture with which Adam reposes. He is not fully animate without a touch from the Creator G-D. This is particularly relvant, in that a white man is being brought to life by a touch from G-D. If others are not privy to the same touch and relationship what are they left with? Do they remain inanimate? This is why Rosales portrayal is so crucial and helpful. It points to a theologically expansive racial inclusion, not only to the idea of G-D, but to who may be counted among the faithful. This gorgeous depiction of a black female G-D allows for a re-imaging and re-imagining of the white paradigm of god. In another painting by Rosales, the Roman deity, Venus, is depicted being born as a Black gold-leafed vitiligo woman. In this image there are not only normative ideas of beauty, but difference as well. The Black woman’s body is classically proportioned, but not veiled in the classical porcelain veneer. Not only is the racial bias cast off, but the gender constraint along with it, allowing for more of humanity to see themselves as created in the image of G-D. This depiction is throughly counter to the white normative ideal. It is fortifying in its inclusive expansion because in G-D, “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.” Kara Walker also presents a female deity with complex coloration. Her Marvelous Sugar Baby is a black female sphinx constructed out of white sugar. The image is meant to confront and successfully does on many levels: the sugar industry’s past association with slave trade and current culpability in numerous diseases, the oppression of workers rights, and the crumbling edifice of the sugar plant in which the Marvelous Sugar Baby is constructed all point to the derelliction of sinful systems. All of this rhetoric is crucial to the understanding of this massive sculpture as G-D. This is the depiction of a G-D who corrects and points out sin, who graciously and quietly provides guidance to deeper understanding of the sins of omission and the sins of commission. In the work of Walker there is a contemporary imaging of G-D that is very hopeful theologically. It successfully challenges the white normative approach to religious depiction and correctly places culpability and responsibility on the viewer. While these newer interpretations of G-D by Rosales and Walker are not considered orthodox, because of deistic representations outside of the Judeo-Christian pantheon, in The Birth of Oshun and Marvelous Sugar Baby, there are deistic embodiments of race too often relegated to the periphery. This spectrum of depiction allows for a G-D of infinite creation and possibility. A G-D that spoke the world into being in Genesis and with that speech introduced the idea of a creator. From the very beginning humankind has understood itself as a creation. How then does humankinds own creation of imagery affect this understanding of who G-D is? It is important to discuss why the white normative construction of G-D is wrong and must be expanded to a comprehensive inclusion. Humankind is created in the image of G-D. G-D is NOT created in the image of humankind. This reversal, prevalent throughout history, causes the theological limiting and exclusion that is problematic in the visual depictions of G-D. While it is encouraging to see the work of Rosales and Walker, do not be too hasty to say that this is adequate for our understanding of the Divine Mystery. It is still a limited perspective, but does make strides into a more wholistic comprehension. This point is clearly articulated by Saint Paul in his first letter to the Corinthian church, “For now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then we will see face to face. Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known.” Bibliography: Bauman, Guy. "Early Flemish Portraits 1425-1525." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 43, no. 4 (1986): 1-64. doi:10.2307/3269088. Gardner's Art through the Ages 10th Reiss Edition by Tansev, Richard, Kleiner, Fred S., de La Croix, Horst (1995) Hardcover. 10th ed. San Deigo: Harcourt College Pub, 1707. Recht, Roland. Believing and Seeing: the Art of Gothic Cathedrals. Chicago: The University Of Chicago Press, 2010. Scarry, Elaine. On Beauty and Being Just. Reprint ed. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2001. Sherman, Gary D., and Gerald L. Clore. "The Color of Sin: White and Black Are Perceptual Symbols of Moral Purity and Pollution." Psychological Science (0956-7976) 20, no. 8 (August 2009): 1019-1025. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed December 1, 2017). Sayings of the Desert Fathers: the Alphabetical Collection (Cistercian Studies) by Metropolita Anthony of Sourozh (Preface), Benedicta Ward (Translator) (1-feb-1975) Paperback. Kalmazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications; Revised edition edition (1 Feb.1975), 1600. Image Information: Venus of Willendorf (Austria), c. 28,000-23,000 B.C. Limestone, approx. 4 1/4” high. Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna. Accessed December 2, 2017. http://anthropology.msu.edu/anp203h-fs13/2013/11/05/ancient-women-and-art/ Moses of Ethopia. Unknown material and origin. http://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2015/08/the-life-of-abba-moses-ethiopian.html Hubert and Jan van Eyck. The Ghent Altarpiece (closed); completed 1432. Tempera and oil on wood, approx. 11’6” x15’1”. Cathedral of St. Bavo, Ghent, Belgium. Accessed December 2, 2017. https://www.artbible.info/art/lamb-of-god.html Hubert and Jan van Eyck. The Ghent Altarpiece (open); completed 1432. Tempera and oil on wood, approx. 11’6” x15’1”. Cathedral of St. Bavo, Ghent, Belgium. Accessed December 2, 2017. https://www.artbible.info/art/large/317.html Rosales, Harmonia. The Birth of Oshun; 2017. Oil on Linen, 55”x67”. Private Collection. Accessed December 2, 2017.https://www.simardbilodeau.com/fullscreen-page/comp-j7w7halq/f05b8214-69ee-415d-8c42-58d67e8557c7/0/%3Fi%3D0%26p%3Dkqtak%26s%3Dstyle-j7w9xqbi Rosales, Harmonia. The Creation of God; 2017. Oil on Linen, 48”x60”. Private Collection. https://www.simardbilodeau.com/fullscreen-page/comp-j7w7halq/7d70991f-40e4-4232-914d-2f36fa65d4a3/2/%3Fi%3D2%26p%3Dkqtak%26s%3Dstyle-j7w9xqbi di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, Michelangelo. The Creation of Adam; 1512. Fresco, 15′ 9″ x 7′ 7″. Sistine Chapel, Rome, Italy. https://www.lonelyplanet.com/news/2017/10/23/vatican-show-sistine-chapel/ Walker, Kara. A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby; 2014. Mixed Media, 75’x35’. Williamsburg, New York. http://www.contemporaryartdaily.com/2014/07/kara-walker-at-the-domino-sugar-factory/

1 Comment

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |