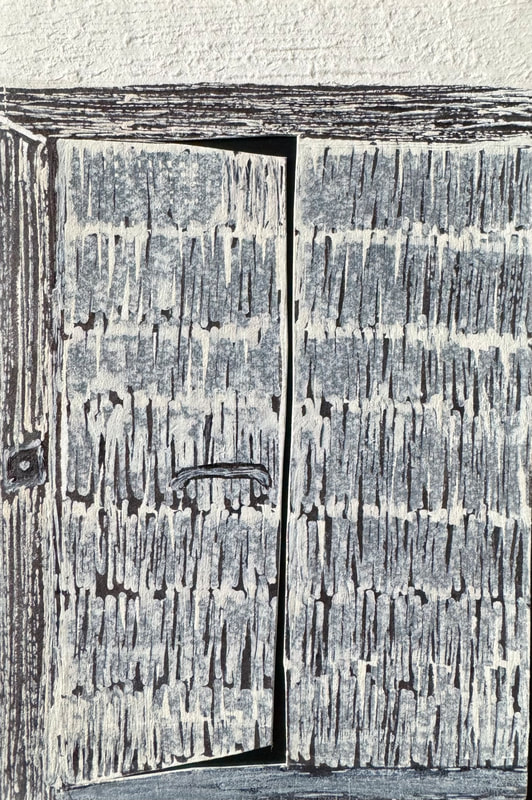

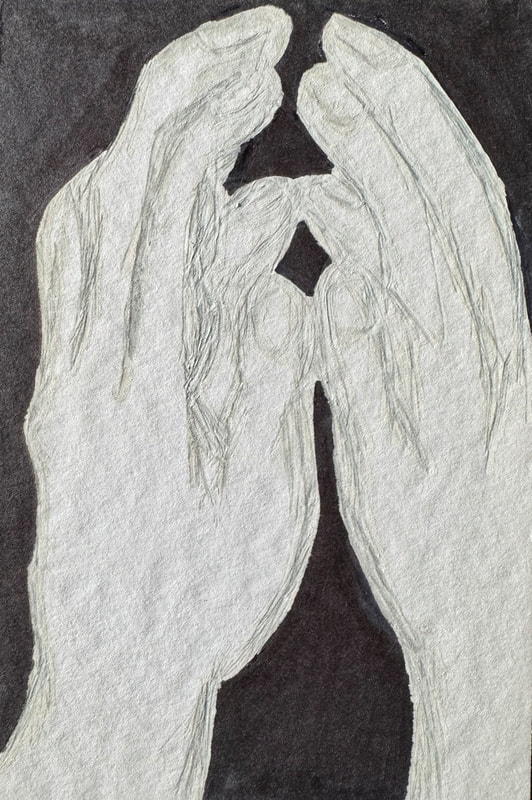

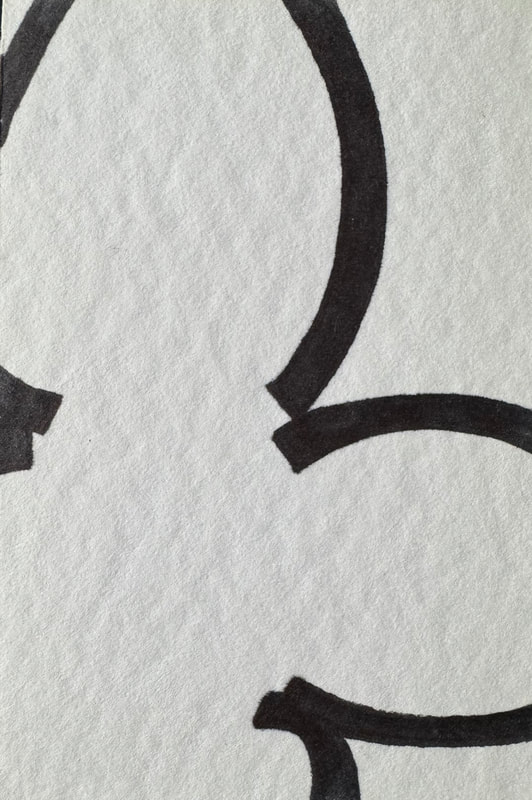

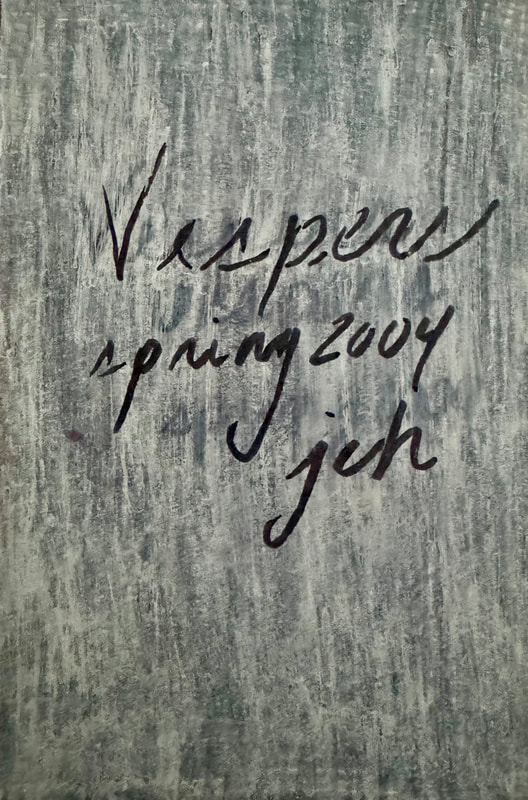

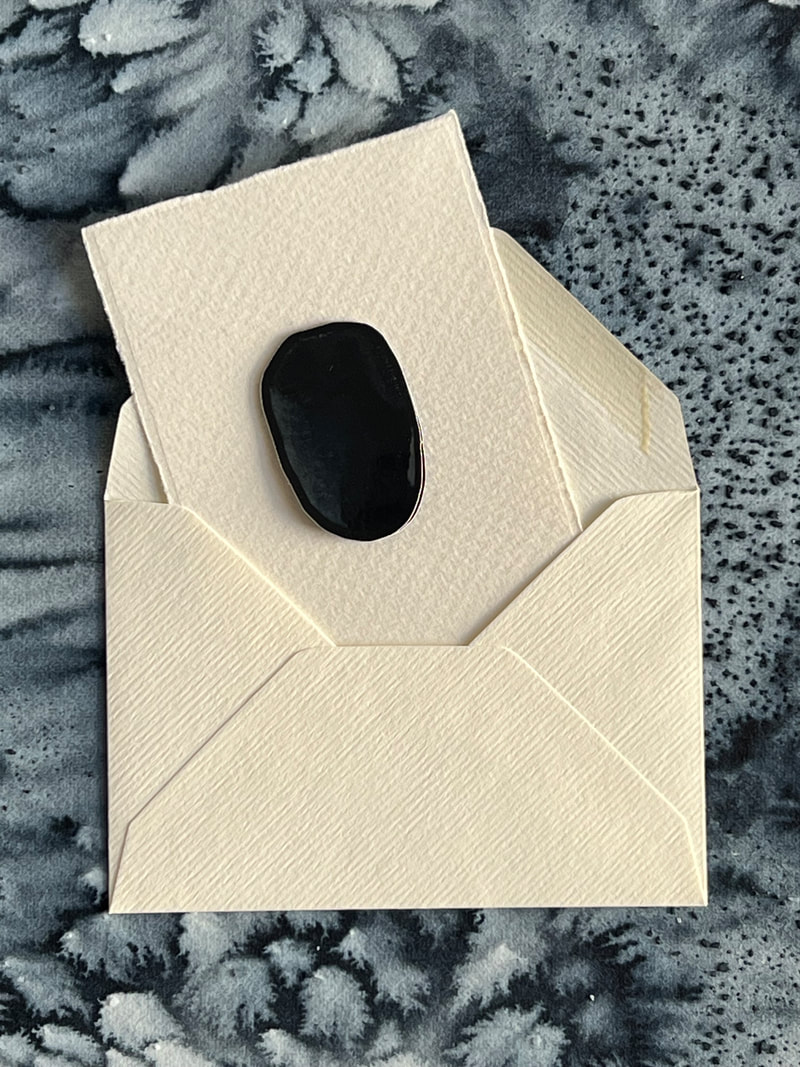

Twenty years ago I had the privilege of studying in Italy as an art student. One of the more remarkable things that semester was the opportunity to participate in a Vespers service with cloistered nuns. Every day I made my way thru multiple doors and gates to pray with these women. On Easter morning, after the Great Vigil, I had the opportunity to meet them for the first time thru the grille and exchange names and pleasantries. It was such an unexpected moment, that I was not prepared for after the solemnity of Lent and the carefully measured and appropriately introspective time and one for which I am immensely thankful.

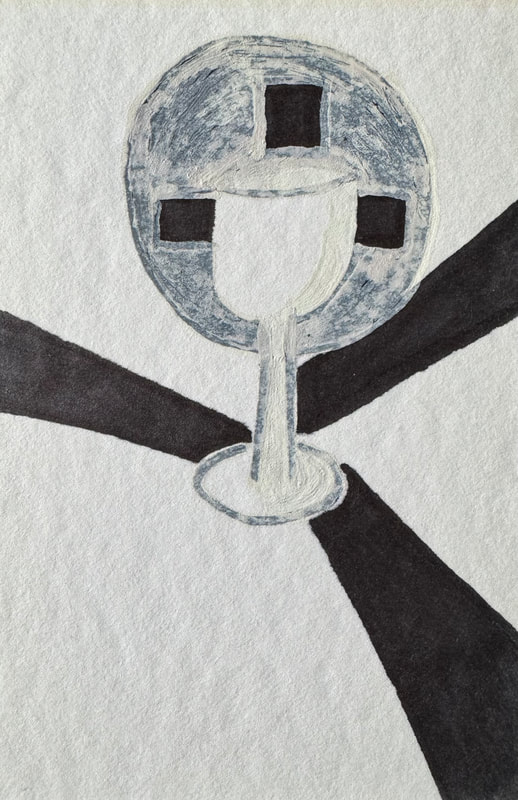

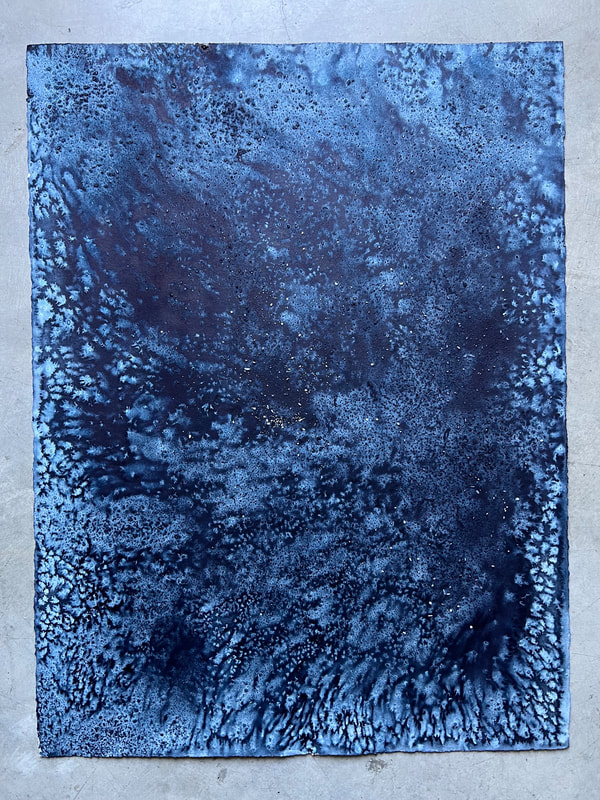

Yesterday I had the opportunity to reflect with Mako Fujimura about the importance of community and relationship for artists. We spoke about the importance of attention focusing on Simone Weil's quote "Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer." and how that connects with the idea of opera Divina. Many creative forces are mentioned and they are linked here:

singer/songwriter Sandra McCracken author of "My Bright Abyss" Christian Wiman composer James Whitbourn organization Goldenwood I have read over my 100 books already this year. Here are some of the standouts:

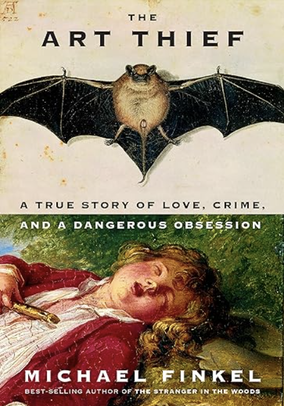

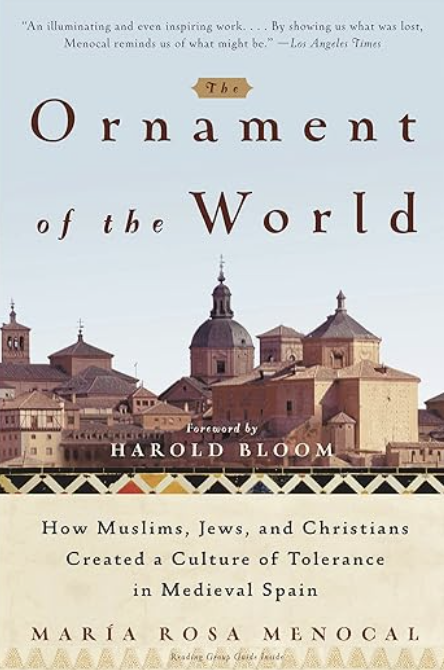

Welcome to the Hyunam-dong Bookshop Hwang Bo-reum A cozy reflection on the role of work and relationship centering around a bookshop serving coffee. Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World Tyson Yunkaporta A necessary offering of a different world-view paradigm. The Vulnerables Sigrid Nunez A fictive narration of how some navigated those first months of pandemic lock-down. The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain Maria Rosa Menocal A beautiful reflection on tolerance, not pluralism, in historical context. The Red Tent Anita Diamant After reading this book, I understand why this book has endured as a popular story, fully realized characters. I Survived Capitalism and All I Got Was This Lousy T-Shirt Madeline Pendleton An insightful first-person perspective on what it means to make a living in late-stage capitalism, while presenting some other options. Oona Out of Order Margarita Montimore A fun time-jumping narrative A Rhythm of Prayer: A Collection of Meditations for Renewal Sarah Bessey An excellent resource and devotional The Evangelical Imagination: How Stories, Images, and Metaphors Created a Culture in Crisis Karen Swallow Prior A clear overview on how the American Evangelical church created its specific culture Unreasonable Hospitality: The Remarkable Power of Giving People More Than They Expect Will Guidara A generous reflection on what it means to pay attention

|